Before the unfortunate and disgraceful event of 22 Bahman 2537 Shahanshahi (Islamic Revolution), those dissatisfied individuals who sought to overthrow the Pahlavi monarchy in Iran through armed struggle or other means were investigated by the military judiciary. After the investigation and gathering of the charges, the accused would be sent to the military court. The accused had the right to be represented by their chosen lawyer or a military-appointed lawyer, who were trained legal officers.

Depending on the severity of the case, the court could have up to three judges, many of whom held high ranks, such as General Zia-od-Din Farsiou, a law graduate of Tehran University and the United States’ advanced judicial training program. These military courts and their judicial processes were part of the justice system of the Pahlavi era. Dissidents, however, labeled these trials as unjust and called the courts “kangaroo courts,” claiming the absence of a jury was proof of injustice. However, even if a jury had existed, these dissidents would have found another excuse. The absence of juries was not unique to Iran; it was common across neighboring countries, including the Soviet Union, most Asian and Middle Eastern countries, and much of Europe and Latin America, and remains an issue today.

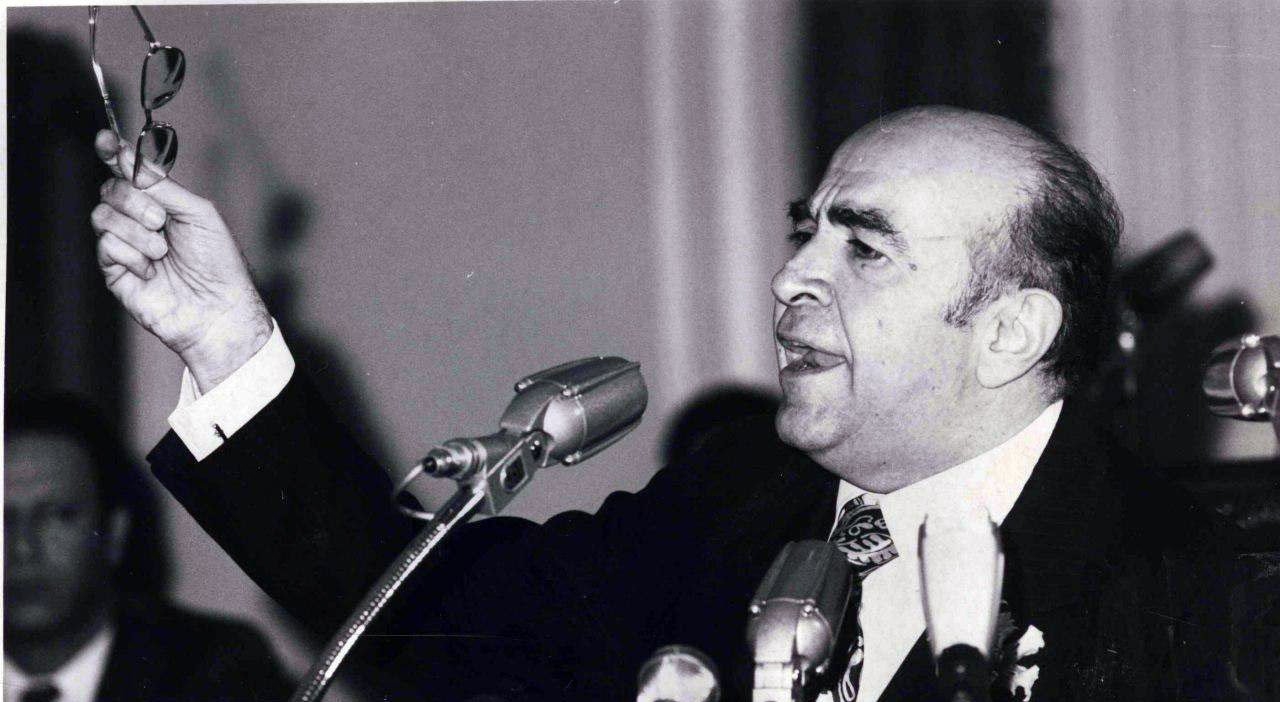

Now, we pose this question: How did the armed and unarmed opposition, which once demanded fair trials with juries in the Pahlavi era, descend to accepting the travesty of “justice” in the Islamic Revolutionary Courts? What kind of trial did the honored patriots, especially military personnel, face when they were executed shortly after the 22 Bahman event? Many of these patriots were either shot during interrogation or stabbed to death en route to the so-called “court.” General Mehdi Rahimi was tortured before his execution, with one of his hands severed. General Badrayi was shot at his desk, and Amir Abbas Hoveyda was shot in the hallway of the “court.” These martyrs were denied legal representation, the ability to present evidence, and were directly sent to death squads. No mention was made of lawyers, evidence-based indictments, or juries for these patriots.

At that time, the “opposition,” both armed and unarmed, not only remained silent about these injustices but often called for harsher and quicker trials. They even celebrated the regime’s brutal actions. Those who doubt this claim should step forward, and we will provide evidence from publications like Keyhan, Ettelaat, and other archival sources of that era to further highlight this fact: “The truth will come out.”

These supposed “defenders of the people,” so caught up in the fever of “revolution,” issued proclamation after proclamation, demanding more “severity” against the remnants of the monarchy. None of these organizations, like the new regime leaders, thought about the future of the country, its security, or its territorial integrity. They failed to realize that the blood they were so unjustly spilling would one day ensnare them as well. It wasn’t long before this prediction came true, as the regime soon turned against Turkmen Sahra, Kurdistan, Arab-speaking areas of Khuzestan, and elsewhere. The same courts that had unjustly sentenced the sons of Iran, from General Nematollah Nasiri to conscript Mostafa Sadri, from Prime Minister Amir Abbas Hoveyda to truck driver Hossein Farzin, were now being used to persecute former revolutionaries.

The difference was that now the “opposition” began to speak out. Left-leaning newspapers like Ayandegan, which had previously called for harsher action against patriots, started to object to these “desert courts” of the Islamic Republic, led by the infamous Khalkhali. Yet when it came to the trial of Mohammad Taghi Shahram, a former member of the “People’s Mujahedin Organization” and later leader of a splinter group called “The Organization for the Struggle for the Liberation of the Working Class,” the hypocrisy of the “defenders of the people” was fully revealed. Taghi Shahram was arrested on July 11, 2538, for ordering the killing of Majid Sharif Vaghefi and facilitating the execution of Samadiyeh Labaf, both members of the Mujahedin who opposed Shahram’s policies. After a year in prison, he was sentenced to death by one of the same sham courts. But this time, the leftist organizations declared that while Shahram deserved to be tried for his crimes, the Islamic Republic’s courts lacked the necessary legitimacy. The Mujahedin themselves refused to comment, only stating that they would accept the legitimacy of the court if one of their own representatives was present during the trial.

The double standards of this “opposition defending the people” in relation to the justice system are glaring. How can a legal process be fair for one group of people and unfair for another? How is it that the execution of patriots loyal to the Pahlavi regime was deemed “just,” while the same courts suddenly became illegitimate when it was the opposition’s turn? While we unequivocally condemn all the crimes committed by these sham courts from their inception to the present, these groups still owe the Iranian people and the families of those executed an explanation.

Based on the bitter experience of the past 45 years, we are convinced that all the so-called trials conducted by the Islamic Republic were nothing but pure injustice. We must learn from this and ensure that in the current and future democratic revolution, justice is upheld and vengeance is avoided. We must honor the memory of the martyrs and break the cycle of imprisoning, torturing, and executing dissidents, so that Iran becomes a just nation where all its citizens are protected.

Bahman 2582 Shahanshahi (Feb 2024)

فارسی

فارسی